Prix des Nations Unies en matière de population

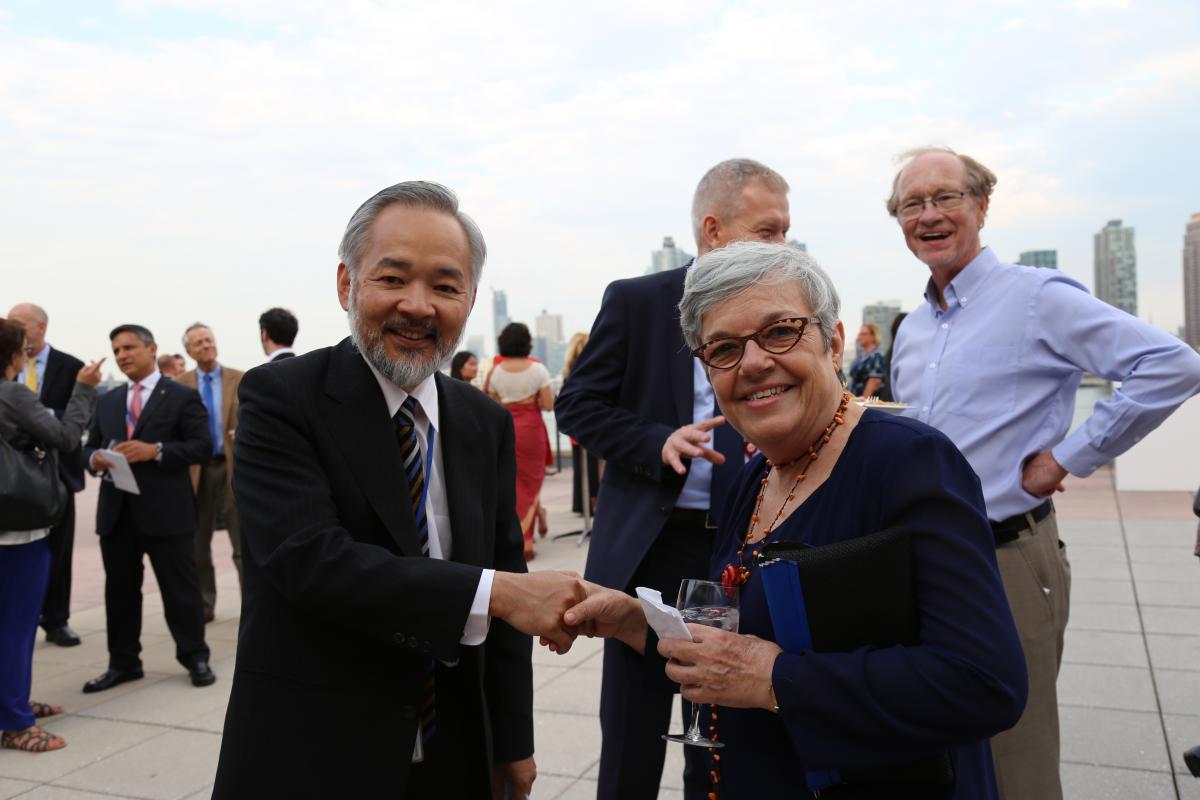

- Discours de la lauréate 2016 Carmen Barroso.23 juin 2016 Carmen Barroso, directrice régionale de l'International Planned Parenthood Federation, Western Hemisphere Region (IPPF/WHR), est la lauréate 2016 du Prix des Nations Unies en matière de population. Le Prix lui a été remis aux Nations Unies le 23 juin 2016. Lisez le discours (en anglais) de Carmen Barroso ci-dessous ou téléchargez-le en pdf.

Acceptance speech by Carmen Barroso: - Mr. Chairman of the Committee for the United Nations Population Award, Mr. Marcelo Scappinin Ricciardi, Chargé d’affaires of the Mission of Paraguay

- Your Excellency Mr. Jan Eliasson, Deputy Secretary-General and Representative of the Secretary-General,

- Dr. Babatunde Osotimehin, Under-Secretary General and Executive Director of UNFPA,

- Members of the Committee for the United Nations Population Award,

- Excellencies, distinguished guests, family and friends

It is a great honour to receive this prestigious award, and I am humbled by the roster of past recipients, many of whom have been heroes and mentors to me and to many others. This award is particularly dear to me because the UN has always had a special place in my life. Its role today is more important than ever in promoting a just world and a healthy planet. I dedicate this award to the anonymous health providers everywhere who, day in and day out, help women to exercise their rights and to preserve their health. To illustrate the role of one of these unsung heroes, I will tell you the story of my so-called miscarriage. The year was 1966. The place was Sao Paulo, Brazil, a country riling under the weight of a military dictatorship. Real and imaginary threats loomed over the most innocent of activities, bathing daily life in a warm fear. Ordinary people tried hard to enjoy the small pleasures of ordinary lives, and, surprisingly, had some success, even when they opposed the ruling of the generals. That was my case. Married two years earlier, I was still in a honeymoon, hardly believing my luck of having fallen in love with Derli, a man so gentle and exciting! Not that it was an easy life. Still a college student, I lived off his meagre salary. Our present was restricted, but we inhabited the future. We had big dreams. We believed social justice and freedom would prevail. We felt part of a movement fighting for a better world. I would finish college and we would pursue further studies in the US. Derli had a scholarship, which he generously postponed until I finished college. We planned to start a family many years later. This vision of the future was essential for our sanity, and we held on to it as if our lives depended on it. And they did. Without it, life under a military regime was too much to bear. Our constrained horizons too tight to allow us to breathe. The future was our protection against apathy and despair. The unwavering belief in our plans was our safety valve. I was meticulous with my birth control pills. But not comfortable with the daily dosage of hormones. A young doctor, who later became a lifelong friend, offered me a way out. He was teaching at a prestigious medical school and had access to IUDs, a method little known in the country at the time. He offered this alternative, which I eagerly accepted. I then started to suffer copious periods with painful cramps. Not one to give up easily, I stuck to it hoping that my discomfort would improve someday. It didn’t. One day I missed my period. I froze with horror! I had been so careful! All of a sudden the castle of my future came crumbling down. I couldn’t find the string of the IUD. Everything pointed to my worst nightmare: I was unmistakably and completely pregnant! I started seeing the man who was my dear husband as the Monster Inseminator who let loose a mischievous sperm that latched on to my defenceless ovum. After the shock, came some clarity: there was one way out. The pregnancy could be interrupted. I had never paid attention to abortion. It was a taboo subject, a subject that remained unspoken at family gatherings and in the church I used to attend regularly. In college, a colleague had mentioned the excruciating pain she had felt in the hands of a back alley abortionist, but that did not register as something that would ever happen to me. Now, the need was clear and imminent. I rushed to my doctor. He saw I was in serious trouble. He cared about his patients and was capable of deep empathy. And … he was very religious. He told me that all I had was a “retention of my period”, the IUD had dislocated and was inside the uterus. He would evacuate the uterus and retrieve the IUD. In retrospect, I believe he created this narrative to calm me down and to justify to himself why he would do something that was against his beliefs, something that could jeopardized his career. And I believed him, because I needed anything that would get me out of the bind. He warned me that – to avoid questions – when registering at the clinic I should say I was having a miscarriage. He also knew we could not pay for an anaesthesiologist. So he gave me medication and told me I would feel some pain, but hopefully it would be tolerable. In that he was wrong. It was hell! But I was so relieved I will be eternally grateful for his support and solidarity. Because of him, Derli and I were able to realize the future we dreamed of. After I got my PhD at Columbia University, I went back to Brazil eager to use my academic work to bring about much needed social change. From my early days of concern with social justice, it was an easy step to gender equality. I initiated a women’s studies centre at the Chagas Foundation despite strong resistance from my colleagues and dear friends, who saw it as a distraction from the real needs of the country, a product of the imperialistic export of feminist ideology. This was very painful for me because these were people I respected and cared for. My resolve to continue was nurtured by the support I got from grassroots women. I was engaged with them through our participatory research. These women reassured me that gender equality deeply resonated with their own needs, and were not bourgeois concerns. The women living in poverty in the periphery of Sao Paulo also taught me some key lessons that shaped my thinking and my career. The Brazilian intelligentsia at that time had an elaborate critique of population policies but had not any alternative paradigm. Population growth was seen as necessary for development and national integrity. Family planning was seen as a Northern countries’ agenda. Dubious practices of over-enthusiastic family planning providers had provoked a backlash. Even the nascent feminist movement was not promoting access to contraception, because it could jeopardize its alliance with the left. Again, the wise women who were barely literate taught me that access to contraception was vital for women of every social class. They gave me the nerve to stand up against the almost unanimous rejection of women’s need to control their bodies and their lives. I have to acknowledge the role of the UN in giving legitimacy to gender issues at that time and opening the space for women’s groups to come out of the shadows. In 1975, the UN celebrated the International Year of Women and convened the First International Women’s Conference. They also helped the creation of incipient international networks of researchers and advocates, which became vital for the pioneers emerging in many countries. For the first time in the history of intergovernmental conferences, a parallel NGO forum was held in Mexico, and I spoke at the first plenary. I was totally unprepared for this opportunity, but I learned a lot in that Conference and got a shot of much-needed energy to face the obstacles at home. My respect for the UN - and its central role in my career trajectory - continued to grow in the following years. First, when I combed its archives for the recovery of the creation of the Commission on the Status of Women in the nineteen forties. Later on, when I became the Director of the Population Program at the MacArthur Foundation, I had a chance to appreciate closely the role played by UNFPA. The Executive Director at that time, Dr. Nafis Sadik, was initially reticent to open doors to NGOs. But she came to Chicago for a meeting I convened of all foundations who wanted to make a case for an NGO Forum. She later became a great champion for civil society voices. While I was at MacArthur, I also had the opportunity to meet the current Executive Director of UNFPA, Dr Babatunde Osotimehin. We travelled together in his home country and I greatly benefitted from his advice and insights. More recently, when I was the Director of IPPF/Western Hemisphere Region, I had the pleasure of collaborating with him to advance reproductive rights when new challenges emerged. At IPPF, I also had the opportunity to work with colleagues from around the world who provide quality services and advocate for enlightened policies at national and international levels. There, again, the UN always was a key element, appearing sometimes in surprising ways. For example, I will never forget my visit with Dona Esperanza, a woman who distributes contraceptives in the remote hills of El Salvador. Pictures of Catholic saints and posters about pills and condoms lined the adobe walls of her home. She provides women with contraception, and she also helps them to defend their rights. She showed me her worn copy of the CEDAW, the Convention of the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. She uses it to convince women, their husbands and the police that it is illegal for a man to beat his wife. That, for me, was living proof of the value of the work done here, day in and day out, by so many of you. During my long love affair with the UN, I lent my support to the GEAR campaign, and we met with Kofi Annan to demand the creation of UN-Women. More recently, I had the privilege of serving in three different panels appointed by Ban Ki-Moon: the iERG on Women’s and Children’s Health; the Advisory Group on the Data Revolution, and the Independent Accountability Panel for the new Global Strategy for Women's, Children's and Adolescents' Health, of which I am now the Acting Chair. In accepting this award, I would be remiss not to acknowledge those who contributed to the paradigm shift that began at the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development. Putting sexual and reproductive health and rights at the heart of population and development policies spearheaded new policies and approaches all over the world. It also helped to unleash a cultural sea change, a new language, and new ways of thinking. Today, the Cairo agenda is still a work in progress. However, no one can deny the impact it has had on countless women, men and adolescents around the world. I was so fortunate to have options when I was so young. This allowed Derli and I to continue fighting for a better future, not just for ourselves, but also for our societies. It also allowed us to have a family when we were ready. Ten years after my so-called miscarriage, the man of my life and I had a daughter, Valentina. I am so happy to see Derli, Valentina and her two boys with my sister here tonight! I would not be here today, were it not for the courage and solidarity of a doctor operating under restrictive laws. I look forward to the day when these unfair laws are changed in all countries where they are still on the books, and when safe abortion is accessible to all women who need it. In accepting the award, I dedicate it to the many people who shared my dreams, supported my struggles, stimulated my ideas; the brave and courageous people who fought for the sexual and reproductive rights of girls and women everywhere. I dedicate this award to the next generation—and especially young people from Carmen’s Youth Catalysts—my namesake youth leadership program at IPPF/WHR—which I encourage you all to check out. I rest my hopes for a more equitable, just, and safe world on your immense enthusiasm and determination to the change this world. All of you are unsung heroes, and I thank you for everything you do. I look forward to the day when equality trumps discrimination, when the horrific massacre of LGBT people and the gang rape of a girl in Rio become distant episodes. I look forward to the world we want, a world where the sustainable development goals will be met, a world where no one will be left behind. A world where the human rights of all will be respected, and a long and healthy life will be achievable for both people and the planet. Thank you so very much! Téléchargez le discours de Carmen Barroso en format PDF. Lisez aussi :

|