Multiple Cause-of-Death Analysis

The IUSSP Scientific Panel on Declining Mortality and Multi-morbidity at Death has put together a series of Questions & Answers about Multiple Cause-of-Death (MCOD) Analysis, clarifying definitions, presenting aims and methods, addressing issues of data quality and international comparison and highlighting the contribution of MCOD to understanding COVID-19 mortality.

Frequently Asked Questions:

1. What are “multiple causes of death”? What about “contributing causes of death”?

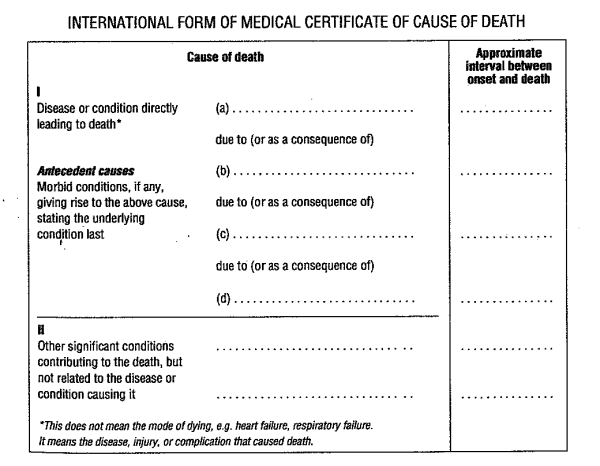

Multiple causes of death (MCOD) refer to the entries listed in the medical part of the death certificate (International Form of Medical Certificate of Cause of Death). The Medical Certificate of Cause of Death is organized into two parts (Figure 1). Part I is devoted to the chain of causes directly leading to death. This includes the disease that initiated the train of events leading to death (also termed “underlying cause” or UC1) as well as consequences of this disease. Part II of the certificate is devoted to any significant conditions contributing to death “but not related to the disease of condition causing it”.

A contributing cause of death is a cause of death present in the death certificate but not listed as the underlying cause. It is possible to classify contributing causes into a few broad categories (See Désesquelles et al. 2012, Grippo et al. 2024):

A growing number of countries produce multiple cause of death data (Bishop et al. 2023). Some countries have multiple cause-of-death data but only for very recent years. This information provides an exhaustive, generally good quality and relatively inexpensive source of data on multi-morbidity at death. ______________________ [1] The selection of the UC relies on the International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD-10) rules. In general, it is the cause that initiated the train of events. There however are some very specific exceptions. As an example, the UC of a death due to liver cancer caused by a chronic liver disease is not the chronic liver disease but the liver cancer. [2] As an example, polypharmacy increases the risk of adverse drug events and non-adherence to treatments.

2. What do multiple causes of death add to the underlying cause of death? What are the aims of Multiple Cause-of-Death (MCOD) analysis?

The measurement of multiple causes of death can be considered complementary to the measurement of a sole underlying cause of each death. Mortality statistics based on the underlying cause (UC) of death have proven to be very powerful for understanding life expectancy trends as well as differences within and between countries. However, in the context of ageing populations and growing prevalence of multi-morbidity, an exclusive focus on the UC limits our understanding of the complexity of the processes leading to death as well as relationship between causes at death.

In addition, trends in the underlying cause of death are susceptible to biases due to changing or country-specific practices of medical doctors in the reporting of certain diseases (e.g. reporting in part I or II of the death certificate). This may be due to changes or variations in the diagnostic practices and the recognition about the role played by these diseases in death (see for instance the case of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in Désesquelles et al. 2014 and Adair et al. 2022). These changes or variations have an impact on how frequently these diseases will be selected as the underlying cause of death. Multiple cause of death analysis can help to overcoming this bias.

The aims of the multiple cause-of-death analysis are becoming increasingly diverse, however, the general aims include the following:

When the analysis is performed using the underlying cause only, the contribution of any given disease or condition in overall mortality is underestimated. Reassessing the burden of a given cause in mortality using multiple cause-of-death data is especially relevant for causes that are rarely selected as the UC. The analysis may take into account the specific role of each cause as stated on the death certificate (underlying or contributing causes or, in even greater detail, “originating”, “associated” or “precipitating” causes - See Grippo et al. 2024).

Multiple cause-of-death analysis provides insight into the combinations of diseases that most frequently lead to death to gain a better understanding of the epidemiological profile of mortality. The analysis may take into account the specific role of each cause as stated on the death certificate. Multiple cause-of-death data can also be used to estimate probabilities of death if one or more causes of death were eliminated. In that case, multiple causes of death help overcoming the assumption of independence between causes that is normally used to estimate the impact of eliminating a cause of death, with the eventual aim of identifying disease patterns that can be considered quite independent of each other such as in the “lethal defect” model of Manton and al. (1976) or in the “relative susceptibility” model of Wong (1977).

With increased life expectancy, death is more often the final stage of a long and complex morbid process involving more than one disease. From a public health perspective, multi-morbid patients represent a major challenge for health systems and caregivers. The number of causes listed on the death certificate can be used as an indicator of multi-morbidity but it does not account for causal relations between the reported causes. A more restrictive definition of multi-morbidity considers a process as multi-morbid if there is more than one independent morbid process described on the death certificate and/or contributing causes in Part II (Grippo et al 2024). It is possible to monitor multi-morbidity at death and to examine causes involved in those processes as well as characteristics of the decedents associated with it (e.g. age, sex…). However, it is not expected that the analysis of multi-morbidity at death provides similar results as the monitoring of multi-morbidity in the living population. The data on which these analyses rely are different both in terms of population (deceased persons vs. living people) and causes under study (causes that contributed to death vs. all causes diagnosed).

3. What are the factors impacting the quality of the multiple cause-of-death data? Can we compare countries using multiple cause-of death data?

The production of multiple cause-of-death data (including the underlying cause of death) relies on two steps that are both crucial for its quality. Firstly, the certifying physician reports the chain of causes leading to death on the certificate. Secondly, this information is coded according to ICD-10 coding rules.

The extent and the impact of faulty certification is difficult to assess (several studies have investigated this issue. See e.g. Guralnick 1966; Speizer et al. 1977; Redelings et al. 2007) but both over- and under-reporting may occur. Certifying physicians may report diseases that were present at death but did not contribute to the morbid process; conversely, they may omit certain diseases that contributed to the death. When the underlying cause of the death (UC) is sufficient to explain the death, the physician may consider that there is no need to describe the clinical course of death in great detail. The certifying physician is required to make a decision about a single etiological sequence ending in death. The International form of medical certificate of cause of death is not adapted to the case of multi-morbid patients for whom the selection of one single etiological sequence is difficult.

The circumstances of the certification (i.e. place of the death and profile/expertise of the person who certifies the death3), the training of the certifiers, as well as how well they apply the skills learnt in training to completing death certificates in practice contribute to the quality of the certification. When the certifying person is the physician who treated the deceased person or when death occurs at the hospital, the information is likely to be more accurate. The availability of accurate information also depends on diagnostic behaviours. More generally, it reflects the state-of-the-art of medical knowledge. Certifying physicians are likely to report only contributing causes which, to their knowledge, possibly interact, with the result that the relationships between diseases already known to the certifying doctor are emphasised, creating a kind of 'confirmation bias'.

Inter-country heterogeneity in the reporting of causes of death is likely. In particular, reporting practices may be influenced by the format of the death certificate. Many countries use adaptations of the WHO recommended death certificate but slight deviations from the WHO certificate (size, number of lines, order of the reporting…) may have a strong impact on the reported data. This is probably partly reflected in the inter-country differences in the average number of entries on the death certificates.

The growing use of the multiple cause of death data by the research community will give the impetus for data collection improvements. Recent developments in the characterization of the causes reported of the death certificate along 4 categories (originating, precipitating, associated and ill-defined) (Grippo et al. 2024) can provide insights into the quality of the cause-of-death data and enable “cleaning” the data in an appropriate way given the objectives of the research.

Regarding coding, a growing number of countries use an automatic coding system to apply ICD-10 coding rules. This represents a major advance towards improved quality of multiple cause-of-death data. The ICD-10 coding rules can be applied systematically and uniformly, irrespective of the coding agent or the country and human intervention is only limited to problematic cases that cannot be processed automatically. IRIS (http://www.iris-institute.org) is a widely used coding system. However, not every country uses IRIS. As an example, the United States uses the MICAR-ACME system. Both systems are highly consistent and strictly follow all WHO rules for the coding of causes and the selection of the underlying cause of death. ______________________ [3] General practitioner, medical examiner, coroner… The certification is not always and everywhere made by physicians.

4. How can multiple cause-of-death data be analyzed?

Methods and aims of MCOD are becoming more and more diverse (see Désesquelles et al 2012, Bishop et al 2023). Several general approaches have been developed, including the following:

Depending on the aims of the analysis, it can be useful to distinguish between causes in Part I and causes in Part II as they correspond to different roles in the morbid process (See Trias-Llimós et al. 2023). It may also be useful to distinguish between causes depending on the role they played in the lethal process (See Grippo et al. 2024). The results of multiple cause of death analyses can be visualised in several different ways depending on the intended purpose.

5. How can multiple cause-of-death data improve our understanding of mortality in the COVID-19 pandemic?

The characterization and understanding of the mortality related to COVID-19 have much to gain from analysing all entries on the death certificates (Petit et al. 2024). More precisely, it can be used to:

Selected references

|